Jay Bryan: Inevitable housing crash? It's been called off

At a time when job growth in Canada is throttling back, as consumer spending slows, we're going through a delicate transition that could be badly derailed if there were a hard landing in real estate markets.

Just out of curiosity . . . what is the point of an article (editorial?) like this anyway? Comment fishing can't be worth this embarrassment. Appeasing the Real Estate Advertisers is the next most reasonable explanation I can come up with.

And I love how the only meaningful number cited is the 10% overvalued as opposed to basic journalism which would involve presenting countering stats. He doesn't even bother summarizing how the 10% calculation came about (I've never seen it accompanied by an explanation, so maybe there isn't any).

Yeah, Mr. Bryan, the market is a mere 10% overvalued after going up that much nearly every year in the last decade while inflation was less than a third of that.

Let's recast it this way: Let's say you are divorced and paying alimony. And every year since 2000 the judge has ordered you to pay your wife 10% more than the year before. If you and your friends are out at the bar drinking, would you assert to your drinking buddies that your wife's share of your monthly paycheck is only 10% overvalued?

Doesn't that sound foolish?

Pro-tip: the need for the "delicate transition" (that must be an economic term of some kind) is caused by misallocation of capital, into houses. If houses are so amazingly perfectly valued, you wouldn't be fearful of government policy damaging the value. You've just undermined your entire assertion by screaming "Hey, don't blow on that house of cards. That would be a really bad idea right now while the rug is on fire and the dog is eating the cat!"

While we're now getting a growing boost from exports to the thawing U.S. economy, the slowdown in consumer spending on housing needs to be gradual if Canada's growth is to avoid a shock. Happily, this is pretty much what seems to be happening.

Yes, and when the speculative component is gone from the market, people will still totally be cool with paying twice as much as an American for the same shelter. On lower post-tax income, no less. What troopers.

A few cities, including Montreal and Ottawa, saw bigger sales declines, but their prices remained firm. rising a little faster than the national pace of 2.7 per cent for the past 12 months.

Oh yeah. Year on year we're good, folks. Nothing to see here. Montreal is down 5% just since July, but all's well. And hey, it's only 10% overvalued. So we're halfway there. Yippy. (And I know the production of your little advertiser happy meal wasn't meant to take up too much of your time, but you need a comma there, not a period.)

Not coincidentally, Toronto is the one market with a segment that could be flirting with speculative instability, suggests Douglas Porter, deputy chief economist at BMO Capital Markets.

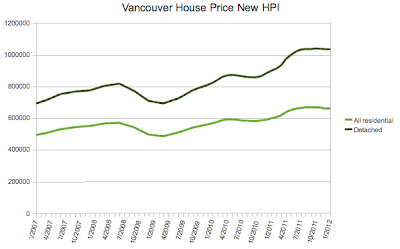

Great news, those 10.5x income to price ratios in Vancouver are totally reasonable. Montreal, of course, with it's median multiple up 60% since 2004 to 5.1x (according to demographia) is not a bubble, either. Mr. Bryan wouldn't miss a bubble in his own back yard, would he?

Still, the broader market looks increasingly sustainable as price gains slow down to a national pace that no longer outruns people's income growth, Porter notes.

"No longer outruns" So . . . there is no reckoning for the previous binge on mortgage debt? Canadian households are just going to limp along under record debt loads, sacrificing stuff for their kids, vacations, etc, forever?

Given this benign outlook, it's a little baffling that we're still seeing scary reports about Canada's bubble - a situation where price gains accelerate as they feed on themselves.

Sorry, what's baffling? You just said it. Prices outran income, employment is shaky, and now carrying costs and debt are going to crush consumers. It's called an unwind. You imagine it will happen in an orderly fashion based mostly on the assumption that the overvaluation is small. Your tiny dream overvaluation which is already exceeded by the declines in Edmonton, Victoria, and Calgary. But you don't supposition that all's well nationwide because some places have already adjusted that whole amount. Why not? It's almost like you don't actually know that.

While it's sad to see a renowned publication [the Economist] sink to such a level, perhaps it's not surprising.

I agree, calling it a balloon is comically silly. When you let go of a balloon, what does it do? Flies around smacking into all kinds of things. You are hanging your hopes on a METAPHOR. On the other hand

my metaphor can beat up your metaphor might make a cute bumpersticker . . .

Porter, who's been tracking all the predictions of disaster with bemusement, theorizes that people just can't understand why, if the U.S. had a huge crash, next-door Canada had its own big housing boom, but no crash.

It's not a mystery. 40 year amortization with 0% down. Securitization of 90% of mortgage debt growth over the last 4 year. Banks giving 7% cash back on a 5% down mortgage. Mystery solved.

The answer, of course, it that a bubble-and-crash cycle isn't easy to produce.

What? Since the dawn of civilization, bubble and crash cycles have been the norm. But they are hard to produce. That's new.

First, a true speculative bubble requires impressive levels of irresponsibility from banks and regulators, something that took a long time to develop in the U.S. Canada never matched this achievement. A mere 10-percent or so of overvaluation, which is roughly what we have in Canada, is no bubble.

Show me the fiscal irresponsibility in Ireland, in Spain, in the UK. Bad news, buddy, the problem is overextending credit, period. Subprime and mortgage fraud simply broke the back of the system sooner in the U.S. You will please note that Jumbo mortgages (in excess of $1 million, all Prime mortgages issued to people more than able to pay, and still able) lead the growth in foreclosures right now. Up nearly 600%. Overextended buyers will not keep paying once those dreamed-of gains vanish. Once people realize there is no "investment" in buying a house, they will realize they are no more than renters paying too much rent, and carrying all the risk, unlike a real renter.

Apart from some overheated niches in the market, history suggests to him that we'll likely see home prices that simply go sideways for several years, allowing incomes to catch up.

"History suggests?" Really? Porter should point to a single case where this has happened, you know, in history.